Popular Roman dress: the 'minenti'

In Rome, in the early years of the 19th century, the term 'minenti' was used to describe the wealthy commoners, i.e. artisans, carters and workers who had become fairly well-off thanks to the income from their jobs. The economic well-being they had achieved was deliberately flaunted, especially by their wives, by means of flashy and opulent dress.

There have been various studies concerning the etymological meaning of the word minenti. For example, the lawyer Luigi Dubino, author of the Elenco di alcuni costumi, usi e detti romani (1875), claimed that the word was derived from Eminenti (from the Latin eminens-eminentis -apparent, sticking out) and meant the commoner, but more frequently the commoner (minente) who dressed ostentatiously, flaunting numerous gold jewels.

Costantino Maes, (1839-1910) editor of the weekly magazine "Chracas" from 1887 to 1894, proposed the derivation from minantes, or mincing, because of the somewhat boastful and rash manner of the authentic Roman, or from minores gentes, the lesser people.

Finally, Valentina Leonardi, in Il Santuario del Divino Amore, 1976, writes: "...minentes has precisely the meaning of popolino (little people), it designates the mass of minute artisans (etymologically from minorentes for syncope as opposed to maiorantes, the mayors who in the 11th century were distinguished by the title of Stimolantes, that is, they had the task of preceding the papal procession by making way through the crowd with their sticks".

The basic elements of the Minente's festive dress were: the long-sleeved velvet jacket (carmagnola) decorated with lace and tassels, the sleeves of which were bulging at the shoulder and embellished with puffs and ruffles; the ankle-length velvet skirt, thickly gathered at the waist at the hips; the silk apron decorated with lace; the white socks; the low shoes ('pianelle') decorated with silver buckles like those for men.

Young women adorned their hair with a high comb decorated with fretwork and stuck a silver pin (tremolante, fiore, spadino) in the braids. The head of the pin evoked phytomorphic motifs or apotropaic symbols and was used to offend.

Older women wore their hair gathered in a green silk net, from which hung a long cord ending in a bow. A distinctive element of Roman women's festive dress, however, was the tuba or bowler hat, both decorated with flowers, coloured ribbons or chicken feathers. The black or brown tuba hat was called "rammoschè" from the French rat-musquè (muskrat) to indicate the fur of the animal from which it was made.

Finally, the minenti adorned themselves with numerous gaudy jewels, which the Rome weekly 'Chracas' described in 1889 as follows: 'The minenti shone with gold necklaces, gems and precious stones, their necks and breasts were covered with gold chains, and their ears were covered with long scioccaje (large beads) made of very large pearls, real oriental pearls. Gold, diamonds and false pearls, the luxury of modern poverty, were abhorred by plebeian opulence. Jewellery condensed enviable sums of money into a short space. Both males and females had four or five rings on each finger; men, in addition to solid, heavy gold chains for their watches, wore massive silver buckles on their shoes and gold earrings that looked like barrel hoops".

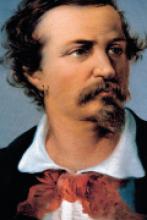

Men's clothing consisted of a shirt, preferably white, with long, wide sleeves, generally worn rolled up at the forearm; a neckerchief; a velvet or cloth waistcoat; a short jacket, also made of velvet or cloth, which, as Father Antonio Bresciani wrote in 1860, was worn slung over the left shoulder so as not to hinder the movement of the arms, so as "to be able to defend themselves if necessary"; the trousers were knee-length with a side opening closed by buttons and/or buckles, while the fastening at the waist was made up of a flap closed at the front and sides by buttons; the stockings were white or sky-blue; the shoes were low, square-toed and decorated with gaudy perforated silver buckles; the hips were tightened by a multi-coloured silk band with the ends decorated with fringes; finally, there was a wide-brimmed hat decorated with capon feathers.

The coachmen, who transported wine from the Castelli Romani to the city, travelling at night along the Appian and Tuscolana consular roads, wore clothes that immediately identified them with their profession. They were functional and protective garments with respect to the risks of a job that exposed them to dangers and bad weather. This clothing included a large cloak (ferajuolo) made from a rough woolen fabric (borgonzone) which, as Massimo D'Azeglio wrote, was "...all length and no figure"; a truncated cone-shaped hat adorned with ribbons of bright colours and capon feathers; gaudy gold hoops at the ears and a coloured sash at the waist. On their feet they wore leather leggings, fastened at the sides by means of buckles. On their shoulders they carried a small cask (copella) full of wine tied to a chain, which was the host's gift of wine to the carter who supplied him.