The laundry

The family based economy of the working class in Rome in the Nineteenth Century meant that every member of the family worked to contribute to the sustenance of the family. Women mainly found jobs in the textile industry (weaving, spinning and sewing), the clothing industry (dress makers, stocking makers, seamstresses and hemmers) and, particularly after 1860, in the tobacco factories of Trastevere, where they worked “sigaraia” (cigarette makers).

Those who were not employed in one of these sectors found domestic work as servants or laundresses.

The laundries – public places fitted out for the washing of clothes – were spaces used mainly by women (laundresses or washer women), who, as their job, washed everyone’s clothes.

The tools of their trade were pieces of solid soap, wood ash, the washing table, the “colatoio” – a terracotta bowl, perforated at the bottom, the wash tub, the hemp canvas (ceneraccio), the jug (broccuccia), the bowl, the cauldron, the stove, the metalware (cazza), and the forked wooden stick.

To clean and whiten the wash a special liquid was used, made at home, using boiling water and wood ash, which was called “ranno” and could be gentle or strong depending on the quantity of ash added to the water.

This liquid, like soap – which was made using residual fats – was one of the few things whose production, until the early Eighteenth century, was not restricted and therefore could be made autonomously by anyone who needed it.

The procedure for doing the wash was as follows: the dirty clothes were washed by the laundry with solid soap cut into blocks, they were then rinsed and wrung out. They were now clean, but not yet whitened. For the latter process, they were placed in a wooden tub, lined with cloth. At the bottom of the tub was a hole, stopped by a plug, in such a way that the water could flow out. Once the cloth had been arranged in the tub, the clothes were laid on top of it, with care being taken to put bay leaves between each layer to perfume the fabric. The water was brought to the boil in a separate cauldron, along with the ash, and was allowed to boil for several minutes. Then it was left to “rest” so that the ash settled to the bottom. The top level of the water was then skimmed off with a “broccuccio” (a small jug with a long handle) and poured into the tub on top of the clothes, which were, however, covered by a sheet, to prevent any ash falling on the clothes together with the water. The clothes, submerged in the water that had been boiled with ash, were left to rest all night. The next morning, the plug at the bottom of the tub was removed, allowing the water to exit. Then the clothes were removed, wrung out, rinsed with water and finally spread, white and perfumed, to dry in the sun.

A figure closely connected to the craft of laundry work was the “Saponaro”, the maker of soap. Until 1600 the oil merchants and soap makers were part of the University of Rome. The two crafts were often effectively carried out by the same people, probably because soap was made using residual fats, either animal or vegetable. They even shared the same Saint, Saint John the Evangelist, because of the martyrdom the Saint suffered, being immersed in boiling water.

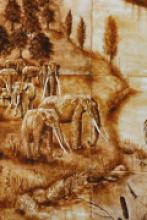

The painting is set in the monumental complex of the del Nazareno where the water carried by the Vergine Acquduct came to the surface. The aqueduct is the only one of the truly ancient aqueducts to have remained unaltered through the centuries. It functioned until the time of Augustus, and even today provides water for the fountains of Piazza Navona and Piazza di Spagna.